I recently had my first encounter with the animal celebrity of this week’s Wildlife Spotlight, the kinkajou (Potos flavus). During a visit to Costa Rica last month, some friends and I stayed up chatting long after sunset.

We were savoring a cool evening after the swelteringly hot days of the dry season in Guanacaste. “Something’s moving in the trees!” my friend cried. We all went quiet and strained to hear over the droning of the crickets. Sure enough, something was rustling high in the canopy overhanging our patio. We all put down our drinks and scrambled to our feet to investigate. I managed to find a powerful field-flashlight and shined it into the trees above us. Two bright yellow eyes reflected strongly back at me from the shadowy branches above.

All at once, a furry creature tumbled off of a branch and into the beam of the flashlight. Hanging by its long, fuzzy tail, it started to casually lick tree sap from the yellowish-brown fur on its forelimbs. It was totally unbothered by us and just carrying about its sticky business. “What the heck is that?!” my friends wondered aloud, while I sputtered off my best educated guesses. “An olingo? Or maybe an olinguito? A kinkajou!?”

I ran to fetch my trusty wildlife guidebook and we soon had our answer. We were face to face with a kinkajou, a cute and little known tropical mammal with some bizarre claims to fame. Let’s learn more about this curious critter and what makes it a unique and adorable part of nature in tropical America.

Cute and strange

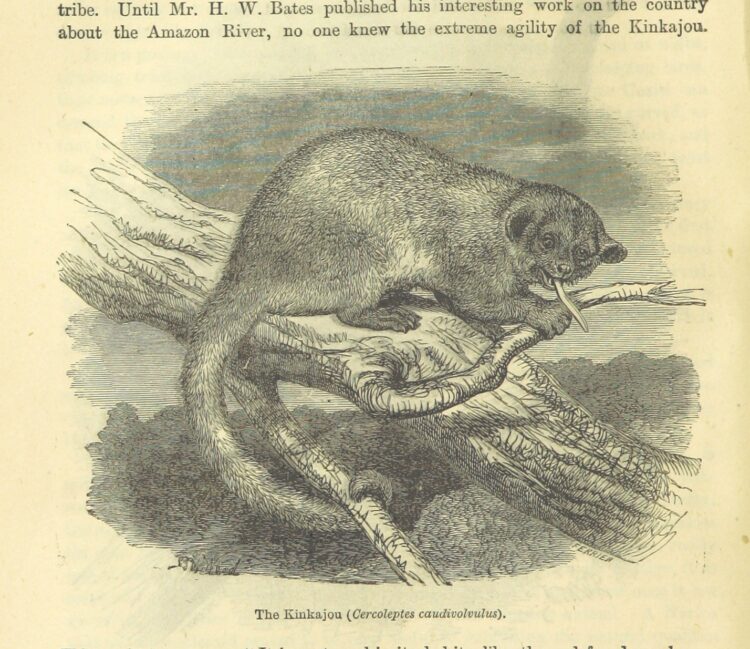

Kinkajous are cute, there’s no getting around that. They are fuzzy, medium-sized mammals about 16-30 inches or 42-75cm long, and weighing up to 3-10lb or 1.4-4.5kg. They are arboreal, meaning that they spend almost their entire lives in trees.

Their tails are long, and they have short, squat, rounded ears that are set low to either side of the head. Kinkajous have short limbs and muzzles and dark eyes which, as I learned, reflect yellow or orange from bright light. They have flexible paws with big toe pads that can grip tree branches and bark.

Now for the weird stuff.

Here are some of their strangest traits:

- Kinkajous have a long, slender tongue that they can extend out of their mouth up to 5 inches (13cm).

- They can turn the ankle joints on their back legs a full 180 degrees, enabling them to move quickly forward or backward when climbing or descending trees.

- Kinkajous have scent glands on their bellies, throats, and by the corners of their mouths for marking trees in their foraging territory.

- Their tail, which can be as long or longer than their body, is prehensile.

A bit more on that last point, because it is especially cool. A prehensile tail can wrap around objects to grip them, acting like a fifth limb. This is why the kinkajou that my friends and I came across was able to hang effortlessly with its back legs dangling while it licked sap from its paws.

Not many mammals have prehensile tails. In fact, that trait is mostly limited to new-world monkeys like howler and spider monkeys. But kinkajous belong to the order carnivora. In fact, only one other mammal out of more than 270 species in that order have a prehensile tail. That is the binturong or bearcat, which is equally weird and will need its own post in the future.

Kinkajou: Mystery beast

Even knowing what a kinkajou looks like, you’re probably still wondering what exactly a kinkajou is. This monkey-tailed, droopy-eared, grabby-handed, chameleon-tongued critter doesn’t fall neatly into any common animal categories. Monkeys might come to mind—don’t they hang by their tails?—or maybe something in the weasel or bear family.

As it turns out, early European naturalists definitely shared this problem. The first reports of kinkajous in Western science classified them as lemurs, which are a unique family of primates found only in Madagascar. They were later re-described as belonging to the civet family viverridae, which are weasel-like mammals found in Asia and Africa.

Perhaps due to this confusion, their common name is thought to originate from the Algonquin word for wolverine. Eventually, taxonomists figured out that they belong to the family Procyonidae, which includes raccoons and some of their shy tropical cousins.

The kinkajou has a pretty awesome scientific name, too: Potos flavus translates roughly to “golden drinker”. The “golden” part probably refers to the color of their fur. Meanwhile, “drinker” relates to their tendency to drink flower nectar and tree sap—read on for more on their diet.

A day—or night—in the life

Kinkajous are nocturnal. In other words, they are most active at night. Field naturalists report that their peak activity is often 7pm or later. During their nightly activity, they emerge from daytime resting or hiding spots and move through the treetops to find food. Their prehensile tails allow them to move easily through the trees with an extra point of attachment. This nightly tree prowling earned them the nickname “night walker” in some parts of Central America.

Mostly a sweet-tooth

The night walkers’ evening patrols are in search of their preferred food, which is primarily fruit. This is also unusual for an animal belonging to the order carnivora. As its name implies, most mammals in that order consume a variety of animal prey. Kinkajou diets, however, are often 90% or more fruits, particularly figs. Much of the rest is made up by leaves, other plant matter, and insects.

Kinkajous, like their cousins the raccoons, will eat small animals and bird eggs if they have the chance, but apparently don’t do it often. They also have a serious taste for nectar and sweet tree saps (hence their other nickname, “honey bear”). No doubt, their long, nimble tongue helps them get at the nectar in large flowers high in the canopy. However, it’s not clear how much of their daily calories they can get from plant juices alone.

Eco-community service

All this fruit-munching and flower-licking ends up having major benefits for the trees on which the kinkajou relies. By eating fruits all over the canopy, kinkajous disperse plant seeds throughout the rainforest. This helps plants move their young to new areas, increasing their likelihood of survival. Seeds end up getting dispersed both through messy eating habits, and when they pass through the kinkajou’s gut and come out in their droppings.

Kinkajous are also messy when lapping up flower nectar. Some tropical flowering trees have massive blossoms, and kinkajous won’t hesitate to stick their whole head inside. This gets them totally coated in pollen, which not only looks hilarious, but means that lots of it gets transferred to the next flower that they visit. In other words, kinkajou’s messy eating habits make them excellent pollinators.

While we typically think of bees or maybe hummingbirds as pollinators, these weird tree-climbers break that mold. In fact, they are the only species in their order that acts as a pollinator. So, just as with their tails, kinkajous set themselves apart with their weird behavior.

A little social

Kinkajous are often encountered foraging alone, but there are reports that they may sometimes roost with other members of their species. They are more likely to appear in groups around concentrated food resources like trees that are blooming all at once, or large fig trees that are heavily fruiting. When hanging out together, kinkajous use a variety of loud and strange vocalizations to communicate with one-another. These spooky sounds, presumably coming out of dark trees at night, led to another of their nicknames in Mexico: la llorona, or the crying woman.

Where can I see a kinkajou?

Kinkajous live in wet or dry tropical forests from Southern Central America to the Amazon in South America. Although a bit secretive, they are relatively common in densely forested areas in the American tropics. You could come across one of these strange treedwellers in forests from Southern Mexico down through Brazil. Of course, if you’re on the hunt for kinkajous, you’ll need to drink up your coffee and head out in the evening.

In particular, kinkajous like habitats with a closed canopy, where they can easily move from tree to tree to cover distance without touching the ground. Their nocturnal lifestyle means that the best time to see them is after sundown. Since their hearing is strong, you may also want to be quieter than my friends and I were when we found one. Or, I guess more appropriately, when it found us. Finding flowering trees, or ones with leaking sap, might also be a good way to set yourself up for success. Kinkajous tend to frequent trees where they can get a quick sugary meal.

Thanks for reading about kinkajous!

Thanks for reading! This post on kinkajous kicks off a series of posts on the bizarre and fascinating world of tropical nature. Although studying the accessible and recognizable nature of our own back yards is extremely important, Earth’s tropical regions hold an astonishing richness of life. This life, often so different from what people in temperate climates are used to, can teach us a lot about the workings of nature. Whether you’re engaging in outdoor travel or you yourself live in the tropics, these posts will have the info and tips you need to enhance your nature experience.

If you have more questions about the kinkajou or a post you’d like to see on tropical nature, let me know in the comments or on the contact page!