Has anyone ever told you that you’re their lobster? After an episode from the second season of the famous sitcom Friends, lobsters have been an unexpected symbol of true love. In episode 14, Phoebe tells Ross that his love for Rachel is like that shared by lobsters for their lifelong mates. “It’s a known fact that lobsters fall in love and mate for life,” she explains, “you can actually see old lobster couples walkin’ around their tank… holding claws!”. As with other wild(life) claims from Hollywood and TV, it’s worth asking: do lobsters really mate for life?

Let’s get to the bottom of it in this Biologist Ruins Everything post.

Lobsters 101

As with any other animal myth, it helps to brush up on some basic biology. For starters, what is a lobster? Specifically, ‘lobster’ refers to several groups of marine or ocean-dwelling crustaceans belonging to the order Decapoda. These many-legged invertebrates are usually omnivorous, both scavenging for prey and hunting it when the opportunity arises.

Like some other species with the same common names, however, different kinds of lobster are not closely related. Since an animal’s life history or way of making a living often influences their mating behavior, it’s good to familiarize ourselves with how lobsters live their lives.

The lobster lifestyle

The lobster with which most people are familiar is the American lobster (Homarus americanus)which is native to the northeast coast of the U.S. and Canada. These and other “true” lobsters belong to the family Nephropidae. Importantly, true lobsters spend their lives under the water along continental shelves.

Lobsters hide in burrows in the sea bottom or under boulders or marine vegetation most of their time. At night, they emerge to feed, patrolling a territory that they defend from other lobsters to make sure they get enough food for themselves.

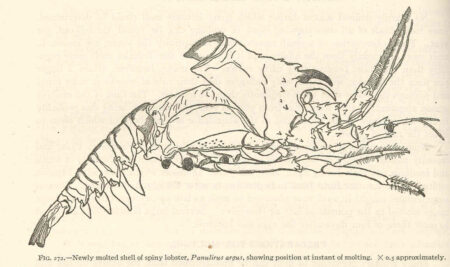

Being arthropods (and more specifically, crustaceans), lobsters’ bodies are covered in a hard, armored shell called an exoskeleton. While this provides excellent protection, it poses challenges for growing animals. As the lobster grows larger, eventually it gets too big for its exoskeleton and must break out in and grow a new, larger one. This process is known as molting. This is a vulnerable period for lobsters, since they are flimsy and defenseless while their shells are still hardening.

Finding love

But why is all this important? As it turns out, these key aspects of lobster lifestyles explain how they mate and reproduce. First off, since lobsters are highly territorial, they are spread out across the ocean floor. This poses a problem for finding mates!

In the American lobster, females are the ones that come a-calling. Indeed, when females are ready to mate, they find a male’s burrow and knock on his door. They do this by urinating, which releases special sex-signaling chemicals into the water. Generally, scientists think that these hormones tell the male not to be aggressive and defend his burrow from the female. However, experimental research suggests that the male doesn’t need his sense of smell to accept her.

Getting undressed

A second obstacle posed by the lobster lifestyle is that all-important armor. As it turns out, female lobsters can’t mate as easily in their hardened shells. To cope with this, they molt after entering the male’s burrow. Next, they mate, and the female stays in the safety of the male’s burrow while her new shell hardens.

Although many people think that the female remains with him during this time due to protection, it may not be the case. In fact, some researchers believe that some of the time she may stay simply because she has to. In other words, while her shell is still hardening, the female is unable to prevent the male from keeping her inside the den.

Sleeping around

Importantly, after the female’s shell is hardened, she leaves the male’s burrow and may go look for a place to lay her fertilized eggs. However, if not all of her eggs are fertilized, she may venture out in search of another male. This way, she can get enough sperm to ensure that all of her eggs have a chance of becoming baby lobsters.

Interestingly, larger females typically have larger clutches of eggs. This means that they need more sperm to get them all fertilized. As a result, they may be more likely to seek out multiple males in order to maximize their eggs’ chance of success.

At the same time, the male is likely to be visited by other females. Although they come one at a time, each cohabitation lasts only a couple of weeks. Because of this, many experts describe lobster mating as serial monogamy. Certainly not the same as mating for life!

The bottom line: do lobsters mate for life?

So, do lobsters mate for life? The short answer is no. Even in other species like the spiny lobsters (family Palinuridae) where males go out looking for females, they do not form pair bonds. In other words, for both males and females, mating for lobsters is a bit of a business transaction, even if an important one.

But does that mean that lobsters can’t teach us anything about love? I think not! For example, one behavioral study showed that lobsters can get romantic without being able to see. That’s right: no vision necessary. If that isn’t a great reminder that love is blind, I don’t know what is!

Thanks for reading about whether lobsters mate for life!

Are you inspired by any other wildlife romances? Is there another nature myth you’d like to see put to the test? Let us know in the comments, or using the Contact page. If you enjoyed this article, please share it via social media and follow Gulo in Nature to stay up to date with the latest posts.