Nature is filled with mind-blowing adaptations. From plants and animals to fungi and microbes, living things display an incredible variety of characteristics that help them get by. Many of these seem absolutely ingenious. In this Deep Stuff post, let’s learn about one particularly cool example: Batesian mimicry.

Seeing is deceiving

One common theme in nature is that often, not everything is as it seems. Pausing to relax in nature or take a sit spot, we often notice hidden treasures. In trying eat or avoid being eaten, many forms of wildlife stay out of sight. Because of this, we may only notice them when we linger a while.

While many living things use camouflage to avoid being seen and falling prey to predators. Organisms that are strikingly visible often have other defenses, like venomous stingers or poison glands. They advertise their formidable armaments with aposematic coloration or warning colors that send a clear message: stay away!

Children quickly learn that the black-and-yellow stripes of wasps, a form of aposematic coloration, can mean a painful sting. If a black-and-yellow bug lands nearby, are they going to take the time to investigate? Unless they’re a passionate naturalist, probably not! Similarly, animal predators learn to associate other warning colors with danger and steer clear of them.

And that’s just what mimics are hoping for!

Mimicry 101

Mimics are living things that have specific adaptations to resemble other organisms. The mimic’s “target”, which it resembles, is called the model. There are lots of reasons to look like other species, particularly if those other species are dangerous. If you look scary, predators might think twice before coming after you. Even if you’re harmless!

That’s the key for Batesian mimics: they “hijack” the warning colors of model species to stay safe from predators. They get all the benefit of looking intimidating, without having to be dangerous for real.

What’s the advantage in that? Well, being dangerous can be expensive! Producing toxins like venoms or poisons takes a lot of energy investment for a growing organism. What’s more, many species just don’t have it in their repertoire to make poisons or other defenses. So their best option is trickery.

In short, Batesian mimics are harmless species that imitate the warning signals of dangerous species to reap the benefits of looking dangerous. If their deception is successful, they are safer from predators than if they didn’t closely resemble their model.

The origins of Batesian mimicry

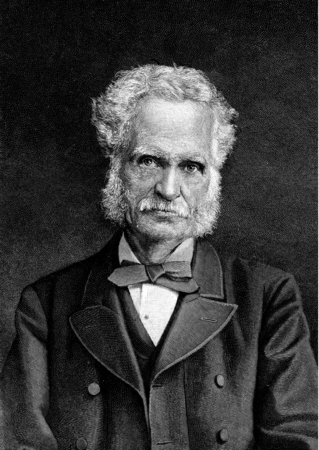

Batesian mimics are named after Henry Walter Bates, a 19th-century English naturalist who was the first European to describe them for Western science. Bates traveled to the Amazon rainforest in the late 1840’s with Alfred Russel Wallace, one of the co-developers of the theory of evolution. While in the tropics, Bates closely studied groups of butterfly species that closely resembled one another.

He found that some species in the genus Dismorphia looked nearly indistinguishable, but that only some were poisonous. This led him to the idea that the harmless butterflies might be safe from predators just by looking like their poisonous cousins.

Examples of Batesian mimicry

Perhaps my favorite example is a lizard species, Eremias lugubris, that imitates toxic beetles in the Kalahari desert. They walk around with a weird, arched posture that baffled many observers. Scientists eventually figured out that they deceives predators into thinking they’re a bombardier beetles, which can shoot scalding hot chemicals from their butts! I wouldn’t want to mess with them, either.

Buzz, buzz

Another great source of examples is the many insects that mimic bees. For example, I once found a large robberfly that looked just like a fat bumblebee. The only reason I knew something was fishy was because of its behavior. Specifically, it would sit around on my friend’s car or a nearby bush and look around as though hunting. Not common bee behavior! This mimic was so accurate that when I tried to identify it with an outdoor app, the app insisted it was a bumblebee. In fact, loads of other users said the same! This goes to show how effective many mimics can be.

Batesian mimicry underwater?

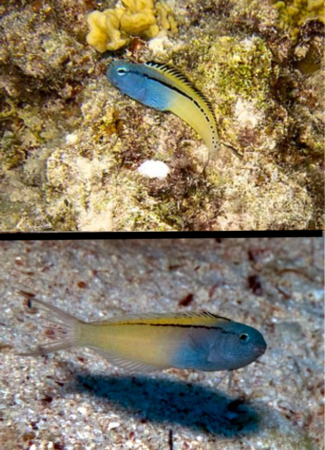

Mimics don’t only live on land. Thumbing through an textbook on vertebrate natural history, I came across a super cool example from the ocean. The red sea mimic blenny (Escenius gravieri), a harmless reef-associated fish, has the same color pattern as the poison-fang or blackline fangblenny (Meiacanthus nigrolineatus). As it’s totally rad name implies, the fangblenny has venomous little fangs and can deliver a dangerous bite! This makes aquatic predators avoid them, and, well, anything else that looks like them, too.

Thanks for reading about Batesian mimicry!

Have you come across other examples of Batesian mimicry in your backyard? Let us know in the comments! Would you like to get a deep-dive into other cool ecology topics from Gulo in Nature? As always, you can let me know using the Contact Page. Thank you for reading Gulo in Nature!