If you’ve looked at any field guide or read a scientific paper in ecology or biology, you’ve probably run into scientific names. These are the fancy, often Harry-Potter-sounding words written in italics and describing a species. Often times you’ll hear them, or read them, after a species’ common name. A friend of mine once told me that to be a real naturalist, a person had to memorize the scientific names of 1,000 species. I’m not sure I agree with that, but a familiarity with scientific names and how they work is definitely helpful for beginning naturalists. This is true both to accelerate your learning about the natural world, and to know what you’re dealing with when you encounter these names in field guides.

What are scientific names for? Where did they come from, and why do people use them? Let’s take a closer look in this Outdoor Tips post. This will be the first in a mini-series of tips to get you started as a beginner naturalist.

What is a scientific name?

Scientific names, also known as Latin names, are standardized names by which we can refer to and identify species. Only one species can have a given scientific name. In other words, they are unique to each species. These names are organized, bestowed, and enforced by societies of scientists. They thus act as official and one-of-a-kind identifiers of species.

For example, the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants standardizes names for non-animal wildlife. When scientists publish research in journals using that code, they need to use the unique names it assigns. When people discover a new species, they assign a new scientific name that is different from all the others. The same thing happens if scientists decide that one species should be split into two or more.

Binomial nomenclature

Two Names

Typical scientific names are composed of two parts. This checks out with the technical term for these names, “binomial nomenclature”, which means “two names”. The two names have a distinct and important meaning beyond sounding fancy. For example, we call human beings Homo sapiens. The first part, Homo, is the generic epithet. This is a fancy way of saying the name of the genus to which that species belongs. The second part is the specific epithet, which is the species itself. A genus (plural: genera) is a group of closely related species, and there can be any number of species within a genus.

Some genera have only one living species (like ours!). Others can have dozens, hundreds, or thousands of species. The genus Astragulus, which includes plants in the pea family known as milkvetches, has over three thousand species! A genus with lots of species can technically be described as speciose while a genus with only one species is monotypic.

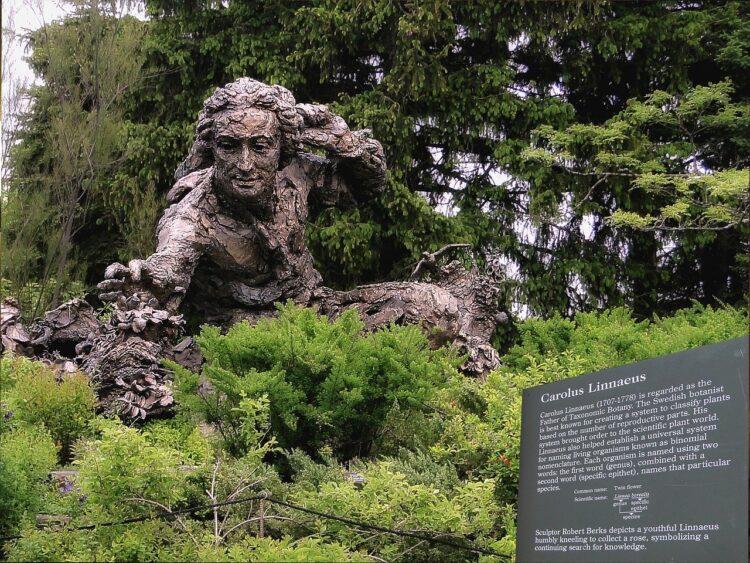

Linnaeus, the Name Guy

People typically credit an 18th-century Swedish naturalist named Carl Linnaeus with developing binomial nomenclature. Although other naturalists were using similar structures for names as early as the 1600’s, Linnaeus’ work in the 1750’s brought it into popular use. His book, Species Plantarum, sorted plants according to genera and species and assigned them unique names.

You may notice that some scientific names are the same word, twice. This blog’s mascot, the wolverine Gulo gulo, is an example. Most of the time this means that the species was the first one in its genus described, or given an official name. For species in Europe, this can also mean that they were named by Linnaeus himself, which is pretty darn neat.

Why do we need scientific names?

Avoiding identity crises

Most importantly, scientific names help us keep track of who’s who in nature. Since only one species can have a given name, we won’t get confused by non-standardized names. For example, what a Londoner calls a robin is totally different than what a birdwatcher in Chicago thinks of when they hear “robin”. While they are both called robin, the British and European bird is known as Erithacus rubecula, while the American one is called Turdus migratorius. If we went only with colloquial or common names, we could get confused really fast. An even more extreme example is the Daddy long-legs, which refers to at least three different critters that are totally different from one-another!

Not only does each species have its own latin name, but they can only have one of these names. This also avoids confusion, because species can have dozens of common names! For example a plant I come across often in Georgia, known locally as the Devil’s Walking Stick, has at least six other common names. You might hear these different names in different parts of the country. Meanwhile its latin name, Aralia spinosa, is the same across the USA and abroad.

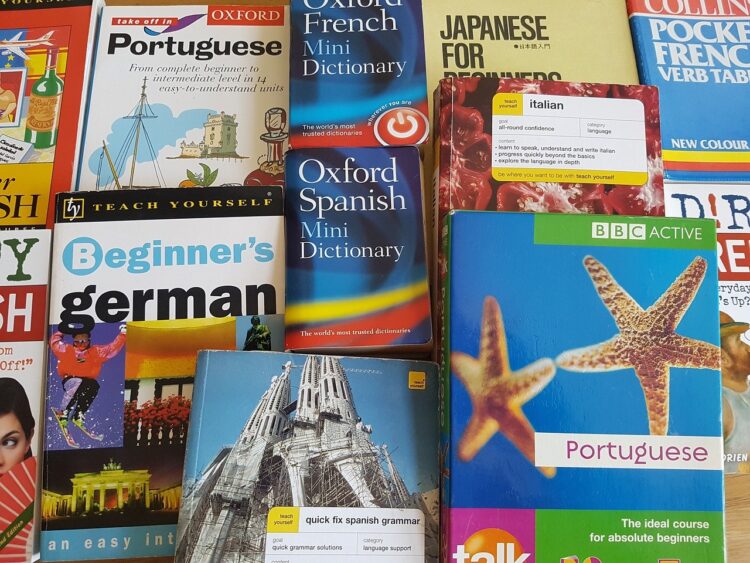

Communicating across borders

Naturalists, scientists, and outdoor enthusiasts are all over the world. They speak many languages other than English, and many dialects within those languages. So even if some species don’t have loads of common names, they will have different ones between languages. Since scientific names are standardizd across scientific societies, they are not tied to a locale. This enables people from different linguistic backgrounds to communicate clearly about species. This has been a huge help for me in my travels as a naturalist and scientist abroad, and avoided a lot of mix-ups.

Even if we translate common names across languages, they can still be really confusing. For example, a gull species named Leucophaeus atricilla is called the laughing gull in the United States. When I lived in Spain, there was another bird called la gaviota reidora, which translates to Laughing gull. However, this was a totally different bird, Chroicocephalus ridibundus, which English speakers would call the Black-headed gull.

Describing relationships

Scientific names also give information on whether species are related to one another. If the first part of two binomial scientific names is the same, then those species are in the same genus. This makes them close cousins in terms of their evolutionary relationships. It means that they diverged from one another relatively recently and that they share certain genetic, behavioral, or morphological traits. Knowing the relationships between different species is a valuable naturalist skill that can help you predict where you might find a given species, or how they might look or behave based on ones you have observed elsewhere.

Bonus information

Scientific names also give additional information about species that you might not get from their names. For example, the Tree swallow (Tachyneta bicolor)’s specific epithet means “two-colored”. While the common name only tells us that this bird has something to do with trees, the scientific name tells us it has two colors: blue and white. You can’t tell much about Plymouth mayflower, a cool eastern wildflower, from its common name. However, its latin name, Epigaea repens, is both poetic and educational. The name, translated partially from Greek and Latin, means “creeping upon the earth”. This is precisely what the plant does, it sticks close to the ground and spreads out across its habitat.

Using scientific names

Although I think you can be a perfectly legitimate naturalist without using scientific names, they can make your observations more precise and, more importantly, accessible to people across language barriers. They also give us extra information about wildlife and their relationships to each other, and so can be worth remembering. So here are some tips for using scientific names as a beginning naturalist:

- Look up the scientific names of new species when you meet them: it’s easier to remember new details when you’re first encountering a species.

- Pay attention to the publication dates on guidebooks and web resources when learning scientific names: scientific names are occasionally changed when species’ relationships are reassessed by scientists, so names from older publications can be out of date!

- Check out the origins and meanings of scientific names when you learn them: this can not only give you cool extra information and historical tidbits, but also give you more to remember them by.

- When you are learning a species scientific name, have a look at other species in its genus: it can be easier to memorize species in groups, and this enables you to remember their similarities and differences.

Writing scientific names

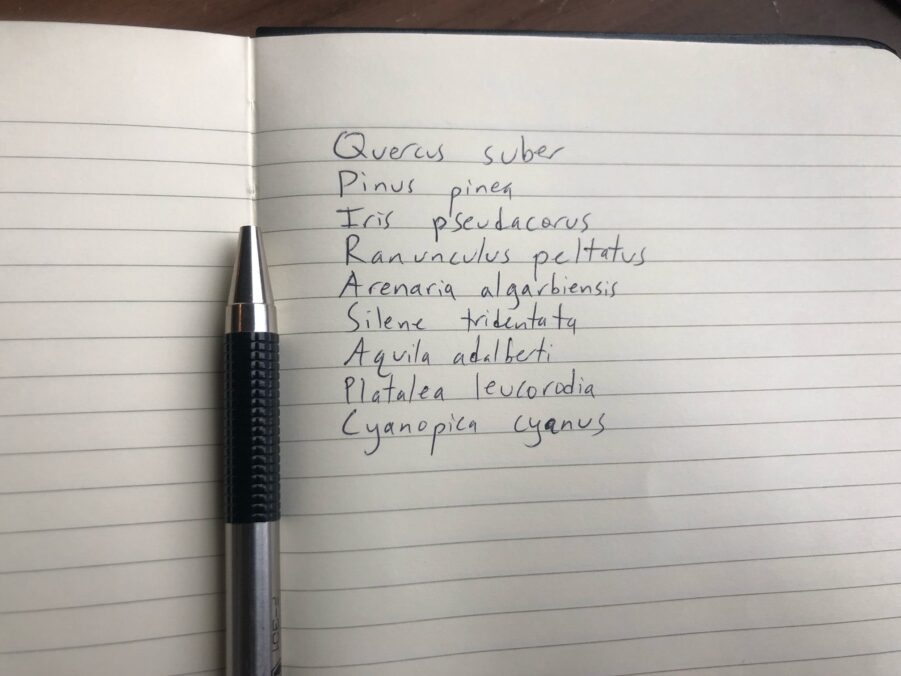

If you plan on using scientific names in your own writing—whether in your field notebook or in a formal publication—it is worth learning some of the conventions for their use. For quick reference, here are some of the common rules for writing scientific names:

- For typed text, write them in italics, or in handwriting like in a field notebook, use underline.

- The first name (generic epithet) is typically capitalized, but the second (specific epithet) is not.

- If you have already used a genus’ name within the text, you can abbreviate it using the capitalized first letter of the generic epithet.

- When referring to a genus in general and not a particular species, you can write the genus followed by “sp.” indicating any species in that genus.

- If you’re referring to several species in a genus, you can use “.spp” to indicate plural species.

- In some formal publications, you may need to mention the “authority” of a species name. This means including the name of the person who described the species, and sometimes the date. This is one in normal text and just using the last name. The last name can also be abbreviated for simplicity. For example, Davidia involucrata Baill. This refers to a tree species, the Dove tree, and the French botanist who described the species for Western science, Henri Ernest Baillon.

How do I pronounce this stuff?

One of the questions people ask me most about scientific names is how to pronounce them. Fortunately the answer is pretty simple: however you want! I have heard some scientific names pronounced dozens of different ways. While some more traditional naturalists take pronunciation really seriously, I don’t think that’s a realistic standpoint. The reason is simple: scientific names are a mash-up of multiple languages with very different pronunciations. For some species, one of their names will be Latin, the other Greek. In many other cases, they include names from indigenous or local languages. The pronunciation of vowel and consonant sounds among these different languages are not compatible, so it doesn’t make sense to say there is only one way to pronounce them. Here are some examples of mixed-language scientific names:

- Grizzly bear, Ursus (Latin for bear), arctos (Greek for bear)—Yes, the literal translation of the Grizzly bear’s name is bear-bear, and that is totally awesome.

- Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus (Greek for hook snout), mykiss (Kamchatkan for, well, Rainbow trout).

- Hawaiian coot, Fulica (Latin for coot), alai (a derivation of the Hawaiian word ‘alae, meaning mudhen).

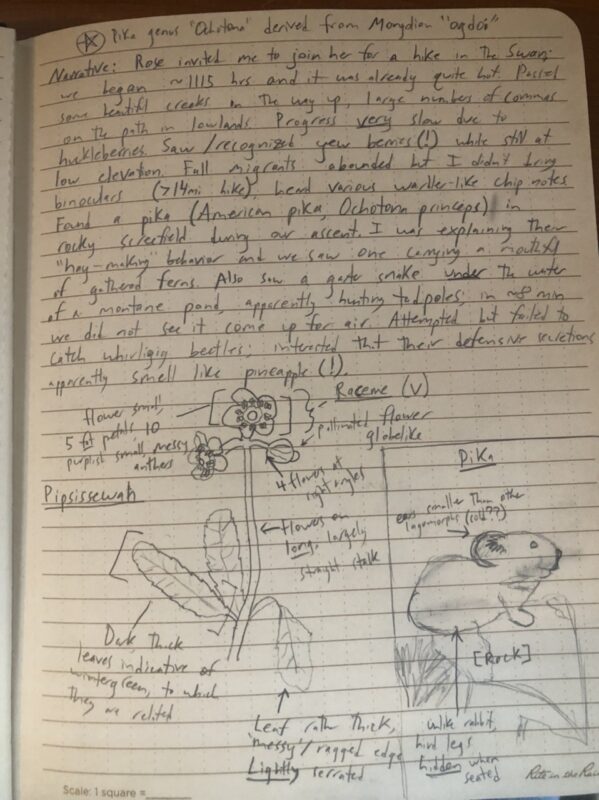

- Pikas, cute rabbit-cousins in the genus Ochotona, get their Latin name from the Mongolian name for them, ogutun–a

So when it comes to talking about latin names, I say pronounce them however your audience will best understand. I often pronounce them in Spanish since that is close to Latin and has a consistent pattern in vowel sounds as opposed to English. This is also helpful when I talk with my naturalist friends in mentors in Spain and Central America.

Thanks for reading!

Now that you know about scientific names and how to use them, you’re ready to add them to your naturalist repertoire. Pulling out some scientific names can be a great way to impress friends and deepen your knowledge on common species.

Do you have other questions about starting out as a naturalist? Are you interested in building more skills to enjoy your time in nature? Let me know in the comments or via the contact page, I’d love to hear from you!