If you’ve ever picked up an ecology textbook or read some interpretive signs in a natural area, chances are you’ve heard of keystone species. People throw this term around a lot when talking about ecosystems, food webs, and conservation. But what is a keystone species? And where did the term come from? In this Deep Stuff post, I’ll give you an introduction to the science of keystone species.

Where did the term ‘keystone species’ come from?

The term keystone species was coined by ecologist Robert T. Paine, a professor at the University of Washington in the western U.S. While studying tidepool ecosystems on Washington’s rocky shores, he noticed that a certain species of starfish (Pisaster sp.) were hugely important. Specifically, by feeding on large numbers of mussels, the starfish prevented the mussels from squeezing out other species for space on the rock surface. In intertidal and rocky shorelines, real estate is super hard to come by.

This is because many organisms like barnacles and algae compete to have a place to fasten themselves and utilize nutrients in the water from a firm foothold. When Dr. Paine removed starfish from these pools, mussels took over quickly and wiped out other species. When the starfish were present, they caused a disturbance that kept a larger number of species around.

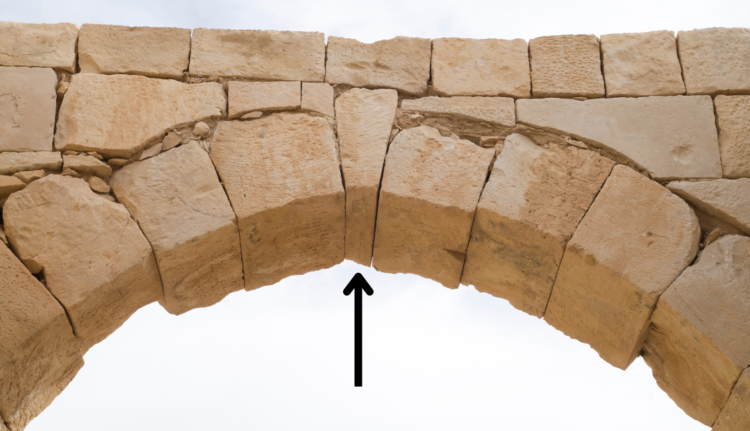

If he removed other species, the results were not nearly as dramatic. This meant that the starfish were performing an especially important function in the ecosystem. In a sense, the ecosystem depended on them. Dr. Paine and other ecologists at the time noticed a similar pattern with other species all over the world. Not only were certain species really important in coastal systems, but also among large mammals in the Serengeti, tiny creatures in tropical rainforests, and so on. Scientists named these organisms keystone species after the central stone in a stone archway.

A helpful analogy

This central stone, which is typically placed last, doesn’t bear much of the pressure of the surrounding structure. However, without it, the arch itself is unstable. All of the other stones have to brace against it. Furthermore, the keystone’s central location illustrates the importance of these species for other forms of life around them. This analogy is the origin of the term itself. Technically, scientists define keystone species as any species that play an especially large or important role in their ecosystem. Secondly, in some definitions, keystone species must also be relatively small in abundance or biomass compared to other organisms.

This concept helps ecologists recognize that different species have different levels of influence on other species. This is an important part of understanding how the natural world functions.

Different ways to be a keystone species

Of course, all kinds of organisms can be keystone species. They don’t need to be starfish. As researchers dug further into this topic in ecosystems all over the world, they found lots of ways that species can be important for their ecosystem. Here are some ways that species can shape their ecosystems:

- Feeding on particular species and controlling their populations (like starfish)

- Altering the structure of the habitat

- Creating resources like space or food

- Providing functions like decomposition or seed dispersal

Keystone species that exert a strong influence through what they eat can easily be found in food webs. They are often apex predators, the highest consumers in the food web. Alternatively, they could be species that are fed upon by a large number of other species, providing a key resource. Let’s look at some examples of different keystone species and how they influence their local ecosystems.

Some examples of keystone species

Seed dispersers

Grey-headed flying foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus) are keystone species in forest habitats in southeastern Australia. These voracious fruit-eaters range widely in search of food, and in the process end up planting seeds for new trees like Johnny Appleseed. This happens because as the flying foxes eat fruit, the seeds of those fruit pass unharmed through their digestive systems.

In fact, in some cases, those seeds are induced to germinate and sprout by passing through the flying foxes’ guts. As they travel, the flying foxes inevitably poop and end up spreading the seeds of many plant species far and wide. This valuable function allows forests to regenerate after disturbance and keeps a larger variety of tree species present in the forest landscape.

Habitat structure

Some species, like beavers (Castor sp.) and corals (class Anthozoa), physically alter their environment in ways that make it habitable for other wildlife. Many corals, which are colonial animals, build extensive structures of calcium carbonate housing thousands of individual coral animals, called polyps. Over time, these structures can grow and stack upon one another as more corals, and more species of coral, build on one another.

This eventually forms a coral reef. There’s a reason that coral reefs are such hotspot destinations for wildlife travel. By creating a three-dimensional structure, much like a forest, in tropical waters, corals build tremendously productive habitat for other wildlife. Algae, fish, crustaceans, and a variety of other animals can only live in coral reefs. They depend on the coral to create their specific habitat.

Breakdown and nutrient cycling

Leafcutter ants in the genus Atta have some of the largest and most complex societies of any animals on earth. Even though each individual ant is small, with colonies that can reach 10 million individuals or more, they can have massive impacts on their environment. Leafcutters, fitting their name, harvest leaf tissue from plants and trees. They cut leaves into small chunks, then bring these back to their nests. Next, they chew and process this organic matter as fertilizer for a fungus, which they farm the way that people grow crops.

This fungus, and associated microbes, are the mainstay of their food. In the process of building massive nests and cutting leaves, leafcutters perform key functions. Just like starfish, they prevent any one species of plant from becoming dominant. They accomplish this by cutting away their leaves, preventing any one species from dominating the available sunlight.

At the same time, they help leaflitter decompose in their underground fungus-farms. In constructing their massive underground cities, which can be as big as 520 square feet (48 square meters), they bring nutrients up to the soil surface. This makes new nutrients available to a diversity of shallow-rooted plants.

A way to conserve wildlife

Keystone species have also become a fantastic tool for nature conservation. If a keystone species is removed from a habitat, the ecosystem will change dramatically. In wildlife conservation, where the goal is protecting ecosystems, keystone species are a helpful tool. If ecologists can recognize which species play a big role in the ecosystem, they can protect those ones first. In doing so, they can concentrate their efforts in a way that may maximally benefit the ecosystem.

In one famous (but debated) case, scientists re-introduced wolves (Canis lupus) to the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Wolves had been driven out by ranchers and hunters in the previous century, and like a tidepool without starfish, the surrounding habitats suffered. In particular, much of the vegetation around streams and rivers was overgrazed by herbivores like elk (Cervus canadensis).

When wolves were introduced, they not only ate some of the elk, but they changed their behavior, causing them to spend less time grazing around rivers. This protected the rivers with a robust buffer of vegetation, which improved water quality for freshwater wildlife. In other words, by protecting and restoring a single species, conservation biologists were able to turn back time and greatly enhance the Yellowstone ecosystem.

There is much more to the story, and new research on this topic emerges regularly. To learn more about the wolf reintroduction and keystone species, check out the Nature Guys Podcast episode “Wolves of Yellowstone“.

Thanks for reading about Keystone Species!

Do you have a favorite keystone species that you’d like to see highlighted? Let me know in the comments!