Invertebrates like spiders, insects, centipedes, and worms are some of the most abundant and diverse living things on Earth. While many people might find them hard to love, these “creepy-crawlies” help keep our planets ecosystems ticking, making life possible for all of us. Whether you appreciate that or not, running into invertebrates—let’s just call them bugs—is a common way that people connect with nature. We can encounter bugs out on a hike, mowing the lawn, in our gardens, or in our homes. It pays to get to know our tiny neighbors, and being able to identify bugs can help us tell helpful ones from harmful ones.

How to know: is this bug in my house dangerous?

Furthermore, just like birdwatching, identifying different insects can be a fun way to get to know your natural world. In this Outdoor Tips post, let’s learn how to identify bugs. Here, I’ll run through 5 questions I use to tell the difference between common groups of invertebrates, and where to go from there.

What is a “bug” anyway?

First things first: What do we mean by “bugs”? Here, we’re using “bugs” in the non-scientific sense. While the word “bug” can be used technically to refer to a large and interesting order of insects that includes the stink bugs, we’re talking about something more general. That is, anything “creepy or crawly” that isn’t an amphibian, bird, fish, or mammal. In more scientific terms, an invertebrate. The bugs that you’ll come across in your house or garden tend to fall into a few major groups:

- Insects (things like flies, beetles, bees, wasps, ants…)

- Arachnids (spiders, daddy long-legs, scorpions, and their relatives)

- Crustaceans (like roly-polies)

- Mollusks (snails and slugs)

- Different kinds of worms (including earthworms, roundworms, leeches, and land planarians)

You can make identification much easier by figuring out which of these groups your critter belongs to. With that information, you’ll know what kind of identification book you should look in, or what section to flip to. Knowing the difference between different creepy-crawlies can help you distinguish harmful from helpful household bugs, and is a great way to get to know your natural world. So let’s go through some quick steps to help you get started identifying bugs in your home, yard, or garden.

1. Does it have legs?

One of the best places to start in identifying a mystery bug is to check whether it has legs. Legs separate a number of common groups of “bugs” from many others that don’t have them. For example, the Arthropods, a huge phylum of invertebrates that includes crustaceans and insects, as well as spiders and centipedes and their relatives, are almost all noticeably leggy.

By contrast, many different types of worms, as well as land-dwelling mollusks like slugs and snails have no legs whatsoever. In short, if you see legs, you’re probably dealing with one of these arthropods, and if you don’t, you may have a worm, slug, or snail. For a bug with legs, continue on to the next couple of steps. If it doesn’t have legs, skip straight to step 4.

This makes legs a particularly valuable clue for dividing up the possibilities early on. However, there can be a bit of a problem: what if you can’t tell if the bug has legs?

Behavior plays a big role in distinguishing all kinds of living things in the wild. Since legs typically play such a giant role in how an animal gets around, watching the way something moves can be extremely helpful. Generally speaking, you can expert smoother, sliding motions, and generally more sluggish (pun intended!) movement from legless bugs. Anything that is hopping, running, or marching along is probably using legs to do so.

But what about flying? That gets us to step number two.

2. Does it have wings?

wings. Among invertebrates, only insects have wings. The only animals that can truly fly are bats (which belong to the mammals), birds, and insects. If you see a bug that is flying, or that has obvious wings, then you have just ruled out a huge number of other possibilities. Great detective work! However, there are two important things to know about insects:

- Insects are the most diverse group of invertebrates. With probably over a million species, they could make up more than three quarters of all creepy crawlies! So, while knowing that something is an insect helps, it certainly leaves a lot more work to do.

- Not all insects have (visible) wings. Many insect species never grow wings (for example, worker ants) or have hidden wings, making it hard to identify them based on that characteristic. As a result, if you see something without wings, that doesn’t necessarily rule out insects.

Although there are a ton of different types of insects out there, by knowing just a few major categories, you can go a long way in figuring them out. If your critter has obvious wings or is flying around, a quick look at some other features on its body or behavior will get you some answers. Check out my guide to these major insect groups, called ‘orders’, below.

Eight insect orders every nature lover should know

What do terms like “order” and “phylum” mean, exactly? Where do they come from? Check out my Beginner Naturalists’ Guide to Taxonomy for a rundown of the basics.

3. How many legs does it (appear to) have?

If you’ve got a leggy bug that doesn’t have wings, you’ll need to find other ways to figure out whether its an insect or some other kind of invertebrate. A ballpark estimate of the number of legs its sporting is a great next step. While you might not be able to get an exact count, especially where some species have legs that are difficult to see, getting a range will be very helpful.

All insects have six legs, however sometimes a couple of them may be hard to see. For example, some butterfly species hold their front legs folded up under their “chin”, making them difficult to see. It makes them appear to only have four legs. Other species may have “tails” or other extensions from their rear parts (abdomen) that give the impression of other legs.

By contrast, arachnids like spiders and scorpions have eight legs, but again some of these can be hard to see. Importantly, any bug you come across might be missing a leg or two, which can also complicate things!

Some rules of thumb for identifying bugs based on their number of legs

- Between 4-6 legs, it is probably an insect.

- More than 6 legs but looks like fewer than 10, it is likely an arachnid or a crustacean.

- If you see more than 10 legs but still an easy number to count, it is likely a crustacean like a roly-poly.

- Anything with too many legs to easily count is probably a millipede or centipede.

What’s the difference between millipedes and centipedes?

4. Does it have an obvious “head” and “tail”?

If you’ve got a legless critter and you’re outside of the tropics, your mystery should be much easier to solve. In temperate regions like North America, Europe, Southern Australia, New Zealand, and much of Asia, your most likely suspects are few in number. These include things like earthworms, which belong to a group called the annelids, and land mollusks like snails and slugs. In tropical regions, land leeches and terrestrial planarians, also known as flatworms, become a complicating factor.

You can tell many of these groups apart by how symmetrical they are front to back. Since most bugs without legs are somewhat elongated, you should be able identify their two ends. If those two ends are similar in appearance, you’ve probably got an earthworm, roundworm, or some other terrestrial worm. A partial exception to this is the clitellum, a thick band of flesh around part of an earthworms’ body, which plays a role in reproduction.

Why do worms come out when it rains?

If you can clearly make out a “head” end, you’re dealing with something else. For example, slugs and snails have a well-developed head with visible eyes and/or antennae which make it easy to tell front from back. Snails, of course, also have their large shells to tip you off! A worm-like body with a fan-shaped or other bulbous looking “head” at one side is a dead giveaway for a predatory land planarian. Although they aren’t common in many temperate regions, there are introduced and invasive species that are becoming widespread in parts of the United States.

Why are invasive species a problem?

5. How is its body shaped?

The general shape of the body, or as naturalists call it, the body plan, can be very different among groups of bugs. If you’re still trying to narrow down a bug with legs, or even trying to distinguish between orders of insects, a look at the body shape is a good next move. Generally, insects have three body segments, the head, thorax, and abdomen. However, these are not always obviously separate in all groups of insects.

For example, beetles’ large wingcases (called elytra) can make their thorax and abdomen look like one big section. Larval insects, for example caterpillars, often have “fake” legs (called prolegs) on their abdomens, which make it hard to tell how many body segments they have.

By contrast, spiders and their cousins the vinegaroons, tend to have bodies with two very pronounced body segments, the cephalothorax (the head and thorax together) and the abdomen. Other arachnid cousins of the spiders, like opilionids (which many call daddy long-legs), scorpions, and vinegaroons only have 1 obvious body segment.

Are daddy long-legs poisonous?

Finally, many-legged critters like centipedes and millipedes might have dozens of segments, each bearing one or more pairs of legs.

Identifying bugs based on body segments: in a nutshell

- 1 segment: Opilionids (harvestmen or daddy long-legs)

- 2 segments: spiders, vinegaroons

- 3 segments: insects

- Many segments: centipedes and millipedes

6. Take a picture

A smartphone camera or any other photo-taking device is a handy resource for a beginning naturalist. Photos can record a lot of visual information that might be difficult to remember later. Furthermore, it provides an easily way of reporting what you saw to someone else. I often learn more about a critter when I can show it to someone more knowledgeable.

Check out more posts on beginner naturalist tips

Collecting a photo will also make it easy to compare what you saw with illustrations or photos in a field guide (see next step), or can be uploaded into a photo ID app. Although less reliable than a field guide for more detailed identifications, smartphones can be quick and reliable for broader classifications. In other words, they can help you confirm whether what you’re dealing with is a worm, an arachnid, or a crustacean, for instance.

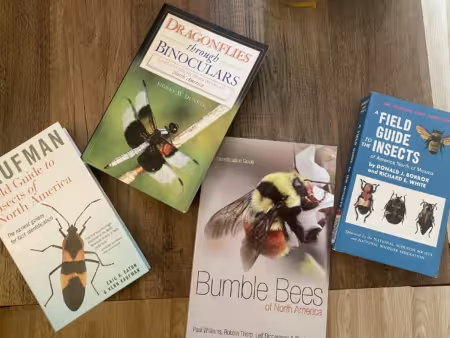

7. Check out a field guide

Spotting an unknown insect is a great reason to head to the bookshelf or library and thumb through some field guides. These fantastic books are an excellent resource for anyone looking to learn a bit more about the natural world. Beyond pictures (often called “plates”) they can have great descriptions of the behaviors and other characteristics of wildlife you come across. For instance, many insect guidebooks have information on what different species eat. With that information, you can figure out how to avoid attracting some animals, or to make them more likely to come to your yard or garden if they are welcome visitors.

Gulo in Nature’s top 5 field guides for birds of North America

Field guides also have great tips on finding animals that you’re interested in, and can provide great background information on whole groups of wildlife. By contrast, many websites and photo ID apps give you very little to go on. Although they might tell you who you’re dealing with, it isn’t very helpful without further knowledge!

Don’t have any field guides of your own? No problem! You can find loads of excellent field guides at bookstores around the world. If you live somewhere with a local library, that could make an even better resource. Collecting useful field guides is a satisfying part of being a naturalist and a great way to learn more about nature when you’re not outdoors.

Check out the “Further reading” section of this post for some excellent field guide recommendations for bugs. You can also check out my curated list of top field guides on Bookshop.org!

8. Try a photo ID app!

Recent years have seen a flourishing of useful outdoor smartphone apps. If you can get a photo of your creepy crawly, these apps can be a fantastic way to get some quick information. However, they can be less reliable than field guides and give relatively limited information about the organism. Nonetheless, they’re a great way to get some quick info and narrow down your search. Many apps also have cool rewards features for logging your sightings and keeping track of how many species you’ve seen.

Gulo in Nature’s 5 essential outdoor apps for nature lovers

My personal favorite for quick ID’s to get my started is iNaturalists’ Seek app. In my experience, it’s a bit less precise than the iNaturalist App itself, but its user-friendly function provides clues in real-time. If I just want to know generally what I’m looking at (for example families of insects, or among orders of invertebrates) it’s a quick way to get that basic info. Of course, there are plenty of other options out there, and they can also be worth exploring.

Download iNaturalist on Google Play

Download iNaturalist in the Apple Store

Generally, I recommend resorting to apps only as a starting point. They can potentially be wrong, and typically only give taxonomic information. That is, they can ID what you saw, but not often tell you important details and context. This information is extremely important for gauging whether an animal is safe to have in your home or garden, for example.

Sources and further reading

Sources for this blog post:

1. Pechenik, J.A. 2015. Biology of the Invertebrates, 7th Edition. McGraw Hill.

2. Headstrom, R. 1979. All about lobsters, crabs, shrimps, and their relatives. Dover Publications, New York

3. Eisner, T. 2003. For Love of Insects. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts.

Some of my favorite picks to help identify bugs

Thanks for reading how to identify bugs!

Have you ID’d any creepy crawlies in your area recently? Share with us in the comments! If you enjoyed this post, please support the blog by sharing this post with friends and colleagues. You can also connect with us on Social Media or reach out using the Contact Page. We appreciate your support!