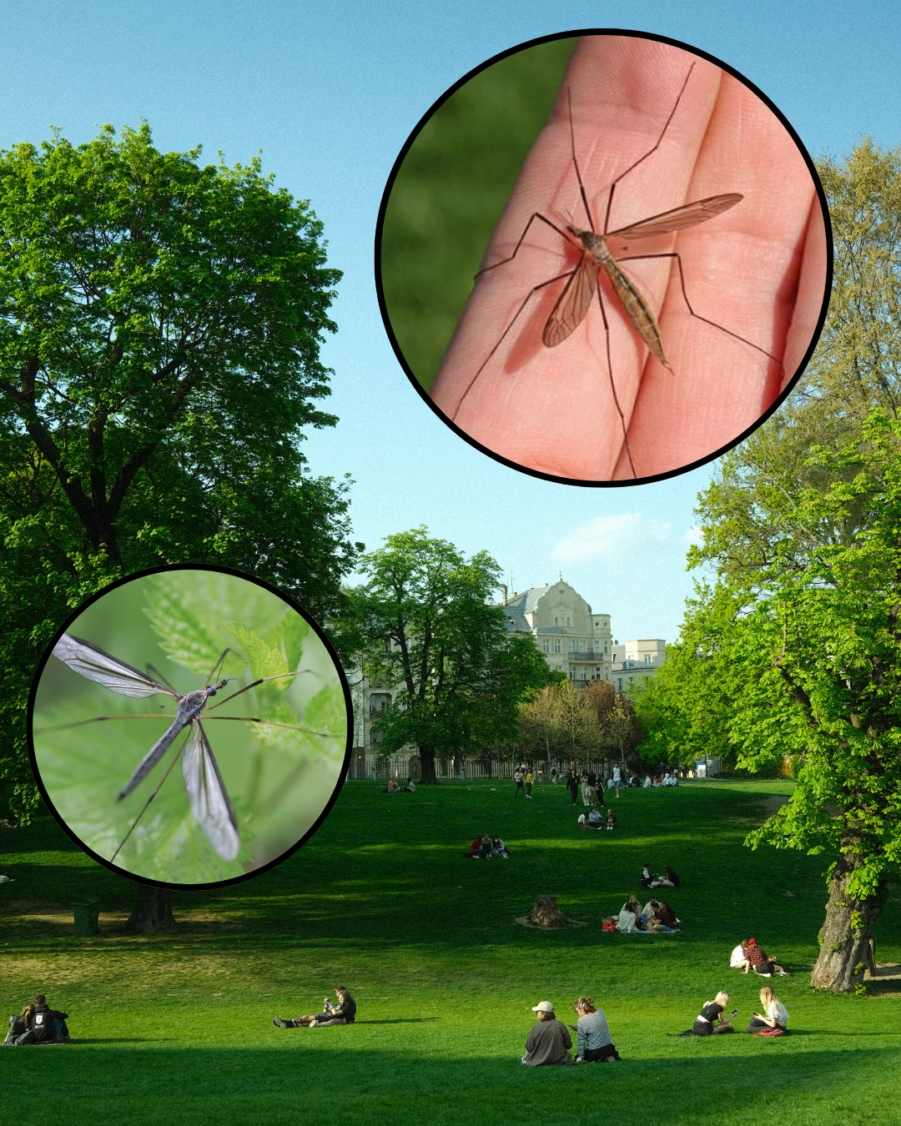

Warmer months anywhere in the world tend to bring out bug of many shapes and sizes. Even if you find them creepy, there’s something impressive about the seemingly endless variety of insects and other invertebrate critters that appear in Spring and Summer. Early each Spring I tend to get a lot of questions from concerned readers and friends about “giant mosquitoes”. People send pictures of large, long-legged flies with elliptical wings and long bodies—a very mosquito-like appearance—and ask whether these bugs pose any threat. In this Naturalist Answers post, you’ll learn about bugs commonly mistaken for giant mosquitoes, and the truth about real giant mosquitoes and where you might find them.

Curious about bugs in your yard? Check out this Guide to Identifying Mystery Bugs!

Craneflies: The Usual Suspects

Most of the time, when people ask me about giant mosquitoes, they end up describing or sending me a photo of a cranefly. These are large-bodied flies in the family Tipulidae which suddenly emerge in Spring or Summer when the soil starts to warm up after Winter. They typically live underground or in bodies of water in their larval stage, which is wormlike and has a tough outer skin. As larvae, craneflies eat decaying organic matter like leaves or rotting wood, and a small number of species with aquatic larvae are predatory as babies, feeding on small, aquatic invertebrates. Some species consume living plant tissue like roots, or emerge from the soil surface to feed on parts of leaves or shoots at night.

Read more: 8 insect orders every nature lover should know

Craneflies are the biggest family of flies on Earth, probably including more than 15,000 species! This makes them the weevils of the Diptera (the order to which flies belong); that is, they have the most species of any related subgroup. Along with this, craneflies are also extremely common and widespread, found in nearly all terrestrial habitats provided that there is enough moisture to support their larvae. Their common appearance has led to a boatload of nicknames:

- Mosquito hawk

- Gully nipper / gallynipper

- Daddy long legs

- Skeeter-eater

- Gollywhoppers

- Leatherjackets (a name used for their larvae)

Read more: Are daddy long-legs dangerous?

Craneflies look very much like mosquitoes, only much, much bigger. And that’s no coincidence! The cranefly family belongs to the suborder Nematocera, which includes mosquitoes, so they are close cousins. This begs the question:

Do craneflies bite?

Unlike many of their relatives, including biting midges and mosquitoes, craneflies do not bite people. Nor do they bite much of anything else, for that matter. Adult craneflies seem to do very little eating, but emerge in warm weather to mate and lay eggs. Scientists have observed some species feeding on nectar from flowers, which would make craneflies minor pollinators. However, adults in the majority of species appear to eat nothing at all!

Do craneflies eat mosquitoes?

When I was a child, I remember older kids explaining to me that craneflies ate mosquitoes, so they were good to have around. Unfortunately, even those species of craneflies which may actually feed as adults don’t do so on mosquitoes. Nicknames like mosquito hawk and skeeter eater show that this belief is widespread. However, craneflies do not eat mosquitoes. They aren’t equipped to chase and subdue prey, but instead are slow, somewhat clumsy fliers with delicate wings and legs.

Where can you find craneflies?

Cranefly larvae are common in moist environments, where they live underground and are generally hard to see. They are often abundant in lawns and gardens, where some species may damage plant roots by feeding on them and other underground plant structures. At very high numbers they can become pests. Because of this habit, craneflies often appear around areas with well-watered lawns and are abundant in parks, college campuses, and suburban neighborhoods. They are also likely a major food resource for lawn-foraging birds like American robins when they build early Spring nests.

Read more: Get to know the American Robin

Craneflies are attracted to artificial lights at night, and are common visitors to outdoor lamps, streetlights and other outdoor light sources. This is especially true during rainy seasons like Spring, which is when I most often hear about them from readers.

Read more: Why are bugs attracted to light?

Do giant mosquitoes actually exist?

Yes, they do! Although the vast majority of giant mosquito sightings are craneflies, there do exist unusually large species of mosquito, and as real mosquitoes, some of these species really do bite. The nastier ones are not fun to deal with, but thankfully most species of real giant mosquito are somewhat rare.

One common species in Eastern North America is Psophora ciliata, an uncommon but intimidating mosquito that shares the common name “gallinipper” with craneflies. Supposedly, the name comes from the myth that they can drink a whole gallon of blood! Although still much smaller than craneflies, they are huge for mosquitoes, with wingspans over 1/3 of an inch (9mm).

These robust-looking mosquitoes match their scary size with very aggressive behavior and a nasty bite. I was unfortunately the victim of one of these during a pause in a morning run in North Georgia in 2022, when I received a surprisingly painful bite through a cotton T-shirt. It hurt enough that I thought it was a botched bee-sting until I spotted the culprit.

Remarkably, Psophora larvae are also carnivorous. While most mosquito larvae feed on particulate matter in little pools of water, these hulked-out mosquitoes are aggressive even as babies! Researchers found that as larvae they can move quickly and use sharp mouthparts to snatch up prey, including the larvae of smaller mosquito species!

What is the largest species of mosquito in the world?

The genus Toxorhynchites, also known as elephant mosquitoes, may hold the record for Earth’s largest mosquitoes. One member of this genus, Toxorhynchites speciosus, a native of Australia, is perhaps the biggest mosquito in the world. They can have a wingspan nearly 3 times that of gallinippers (nearly one inch or up to 24mm!), and have large, predatory larvae just like their North-American cousins.

Fortunately for all of us, and especially Australians, elephant mosquitoes don’t suck blood as adults, but feed on plant sugars that they find in the wild. Given this weird lifestyle switch, scientists believe that female elephant mosquitoes don’t need to suck blood since they get so much nutrition eating other insects while in their larval stage. So, ironically, the biggest mosquito in the world is just as threatening to people as craneflies; that is, not at all!

Read more: The 15 weirdest animals in Australia

Sources and further reading

- Boggs, J. 2023. They’re Not Giant, Mutant Mosquitoes: They’re Crane Flies. Ohio State University.

- Borror and Delong, 1971: An Introduction to the Study of Insects, Third Edition.

- Ragasa, E.V., and Kaufman, P.E. 2012. A mosquito Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius) (Insecta: Diptera: Culicidae). Publication EENY-540. 7 p. Gainesville, FL: Unversity of Florida/IFAS Extension

- Cook, Will. 2025 Gallinipper (Psophora ciliata). Carolina Nature.

Thank you!

If you enjoyed this post, please support the blog by sharing this post with friends and following the blog on Social Media. If you have a post that you’d love to see, get in touch using the Contact Page. Until next time, go get to know your natural world!