Often called “rainforests of the sea”, coral reefs are an iconic marine habitat. Furthermore, they’re a fixture of advertisements for tropical vacations. Tourists are dazzled by the vibrant colors and incredible biodiversity of these busy undersea ecosystems. But what are coral reefs? And how do they form?

In this Naturalist Answers post, we’ll learn about coral reefs, what they are, and what makes them tick.

What are corals?

A good place to start is with what these reefs are made of; that is, coral. Corals are colonial animals. This means that they are not one but a group of independent animals living together.

Unlike living things like individual cells in our bodies, the individual parts of colonial animals are kind of independent. They could survive to some degree without one another.

The animals that make up the diverse forms we call corals are polyps. These coral polyps belong to the phylum cnidaria, a group of interesting and ancient animals that also includes:

- Sea anemones (order Actinaria)

- Jellyfish (Medusozoa)

- Man-o-wars (Hydrozoans)

- Hydras

Coral polyps

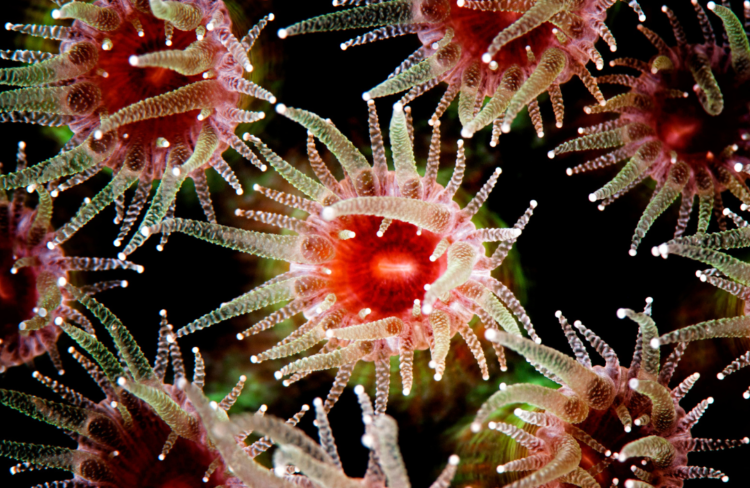

Polyps belong specifically to the class Anthozoa, which are cnidarians that live their adult lives in one place. Scientists and naturalists call this type of organism sessile. Plants might be the most familiar sessile organism to most people, but barnacles are another good example.

Polyps look like tiny sea anemones, and have a chubby, slightly cylindrical body with a mouth on one end. The mouth is surrounded by tentacles that are often equipped with little stinging cells. Just like sea anemones, polyps use their tentacles to gather and subdue prey from the water column.

Since most polyps are really small, they feed primarily on plankton and other small organic matter in the water. Their stinging cells can harpoon and overcome small prey animals, upon which the polyp feeds. However, that’s not the only way that corals make a living!

Partners in crime

Most reef-building coral polyps have other organisms living inside of them. In scientific terms, endosymbionts. In the case of polyps, these are special photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae. Like other photosynthetic organisms, zooxanthellae harness light energy from the sun and convert it to usable food molecules.

The polyp and zooxanthellae are a partnership. Specifically, the polyp provides protection and a carbon source for the algae, and they generate sugars as food for the polyp. During the day, the zooxanthellae photosynthesize and make energy for both they and the polyp. By night, the polyps put out their tentacles and pluck food out of the water column.

This arrangement is a lot like the partnership between fungi and photosynthetic microorganisms that make up lichens. Since most coral polyps are not particularly colorful, the zooxanthellae are often responsible for the more extravagant colors of some corals.

The (literal) hard part

But wait a minute! Coral reefs aren’t soft and squishy like jellyfish. They’re often hard as rocks! How does that work? Being soft and squishy, each polyp actually secretes a calcium carbonate shell around itself for protection. Given the dumpy shape of coral polyps, this forms a little cup, the calyx.

In reef-building coral species, these colonial polyps form thousands if not hundreds of thousands of these little cups. Calcium carbonate, the material that polyps use to build them, is what makes seashells and limestone. As a result, the corals end up building a pretty tough (if not rock-hard!) “fortress” to live in together and live their corally lives.

As the colony grows and individual polyps die, their cups stay behind, and new cups are formed on top of them. Over hundreds and thousands of years, individual coral colonies can grow huge in this way. Looking at any large coral, what we’re actually seeing is many years’ worth of dead coral cups, with a thin layer of life polyps at the surface.

Coral shapes

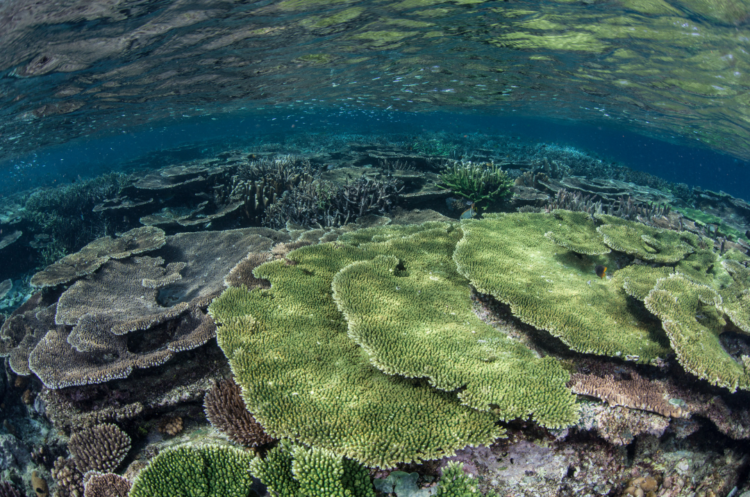

Different species of coral polyps arrange themselves (and their cups) in different patterns. In turn, these give rise to the different shapes and forms of corals that we see in the ocean. Coral shapes are remarkably diverse. The following are coral growth forms you might come across in a reef:

- Branching corals look like leafless little trees with branchlets coming off of larger branches

- Digitate corals look like clumps of fingers or cigars

- Table corals form big, flat horizontal structures

- Elkhorn corals have flattened, antler-like branches

- Foliose corals make thin layers anchored to a substrate like a rock

- Submassive corals have repeated shapes like knobs, columns or wedges

- Cup corals make little clustered cups

- Brain corals make ridged blobs like a big brain

- Massive corals are globular or boulder-like

- Mushroom corals are like half of a dome, like the top of a mushroom

How do coral reefs form?

Coral reefs get started when larval polyps, called planulae, decide to settle somewhere in a suitable location. They are typically looking for shallow, clear water that will give them enough light for zooxanthellae to carry out photosynthesis. The temperatures of the water also make a big difference.

These mobile planulae wander around in search of particular cues that tell them that an area would be a good place to settle. This is a big decision, because once the planulae settle and undergo metamorphosis into a polyp, they’re stuck forever!

When they do make the big decision, the planulae fasten themselves to a surface, and metamorphose into a polyp. At that point, they’ll start growing a calyx with calcium absorbed from the water and taking zooxanthellae symbiotes into their body. The polyp will also begin to clone itself into new members of its colony in a process called budding. Eventually, these will form a large coral colony.

Reef formation

In areas with a lot of steady, solid rock mass for corals to settle, and which have the right light and temperature conditions, this process will happen thousands of times. Dozens of planulae of different coral species will find the location and settle there. Some will even settle on other, existing corals, and build on top of them.

Eventually, this leads to a complete coral reef. This can take hundreds if not thousands of years. In fact, many coral reefs of today are between 5,000-10,000 years old!

Coral reefs most often occur in three kinds of formations:

- Fringing reefs along rocky shorelines

- Barrier reefs, which are further out from the coastline, with calm, tranquil waters called a lagoon between the reef and the coast

- Atolls, which are reefs surrounding sunken islands, with a lagoon in the middle but no coastline at the surface

In each case, corals stack up where conditions are right for their growth. This means the right amount of light, shallow depth, and temperatures that aren’t too cold or too hot. Corals really are the Goldilocks of the oceans!

Where can I find coral reefs?

Coral reefs are mostly distributed in tropical oceans. Although there are many corals that live in colder waters, they typically do not form reefs. The colorful, diverse reefs that we associate with tropical vacations are, indeed, concentrated in the tropics. This is because water in the tropics is often low in nutrients and clear, allowing light to penetrate enough to support corals and their zooxanthellae. Additionally, some zooxanthellae can only survive in a very particular range of temperatures, which can restrict them to milder tropical climates.

The Coral Reef Alliance is a fantastic coral reef conservation organization dedicated to protecting these fragile and important organisms and the ecosystems that they support. Major hotspots of coral reefs are:

- The North Coast of Australia

- The Indo-Pacific ocean around islands like Bali and

- Tropical Pacific islands like the Hawaiian archipelago, Samoan and Marianas Islands

- The Caribbean sea

- The East African Coast

You’ll find the highest density, abundance, and diversity of coral reefs in an area called the coral triangle. This includes Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the Solomon Islands.

Further reading on coral reefs

- Coral Reefs, Secret Cities of the Sea by Anne Sheppard

- Coral Reefs, A Natural History by Charles Sheppard and Russel Kelley

- The Biology of Coral Reefs by Charles Sheppard et al.

- Reef Life: A Tropical Guide to tropical marine life by Brandon Cole

Thanks for reading about coral reefs!

Do you have a coral reef experience that you’d like to share? Let us know in the comments! As always, if you’ve got other nature questions you’d like to see answered on Gulo in Nature, drop me a line using the contact form.