Being a beginner naturalist means learning the answers to lots of what, why, where, and how questions. What is a lichen? Why do bugs gather around streetlights? Where do you go if you want to spot a kingfisher? How do trees move their seeds to new locations? But we tend to overlook questions of when. Nature is dynamic, things are always changing, and often doing so in predictable patterns. As people have recognized in spiritual practices for thousands of years, things often work in cycles. Daily cycles from Earth’s rotation, monthly cycles pertaining to the moon, and annual cycles from our orbit around the sun. Living things are cyclical, too. In other words, what we see in nature has its own rhythms. The study of those rhythms is phenology.

Pheno-what?

The word phenology comes from two Greek words. Many of us already know that ‘Ologies’ are the studies or sciences of something. This comes from the Greek logo, translating as study, discourse, or reasoning. The first part comes from phainein, meaning ‘to bring to light’. It is also related to phainesthai, meaning ‘to appear, which is related to the word phenomenon, a thing that happens or appears.

Simply put, phenology is about keeping track of when stuff shows up.

Scientists define phenology as the study of life cycle events of living organisms. Ecologists and naturalists like my colleagues and I use it for the timing of events within those rhythms. This means paying attention not only to what or where something is happening, but when it happens. Here are some examples of some natural happenings with regular phenological cycles:

- Trees losing their leaves

- Bats coming out to forage at night

- Tropical monsoons

- Temporary wetlands like vernal pools being wet or dry

- Birds migrating (to or from a locale)

- Wildflowers blooming

- ‘Mast years’ of fruiting trees

- The first flights of different butterfly species

- Carpenter bees setting up territories

- Bears going into hibernation

- Spring tides and neap tides

- El Niño patterns of temperatures in the Pacific Ocean

Different tempos

These natural rhythms happen across many different tempos. On the short side, bacterial life cycles can be on the scale of minutes. Many plants and animals change their behavior hourly depending on weather or tidal conditions. On the longer side, migratory animals retreat to low latitudes to overwinter, and return to higher latitudes to breed in summer once every year.

Periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) in North America emerge once every 7, 13, or 17 years. Meanwhile, some plants may bloom only once in their lifetime, and take decades to do so. For example, the Talipot palm (Corphya umbraculifera) in India and Sri Lanka flowers a single time in its life, but can take 30-80 years to mature.

Nothing new

A fancy scientific name doesn’t mean that the study of nature’s rhythms was invented by scientists. People from cultures all over the world have known about timing in nature forever. Just as for any other animals, timing was essential to our lives, and paying close attention to natural rhythms was a part of that. For example, the ancient, traditional Japanese calendar divides the year into 72 microseasons based on the phenology of different natural events.

Forget the Zodiac, were you born during “Safflowers bloom” or “Deer shed antlers”?

If you’d like to learn more about microseasons, check out this great episode of The Nature Guys podcast with special guest Chris Clements of Imago.

Western naturalists, too, have been keeping track of the timing of natural events for millennia. Natural philosophers like Aristotle’s disciple Theophrastus kept careful track of plant flowering dates more than 2,000 years ago. More recently, Henry David Thoreau‘s journals tell us all about when birds and wildflowers showed up in Concord, Massachusetts in the 1840’s. Scientists have used his journals to study how the timing of such events is changing over time.

The importance of timing

Have you ever told a joke at the wrong time? Or misjudged the right moment taking a turn in your car or bicycle, and gotten in somebody’s way? Or had to awkwardly hesitate in front of the revolving doors at a hotel or grocery store? Yikes. These are all good examples of bad timing. For many things, there’s a right time for them to happen, and plenty of wrong times.

I see this principle at work all the time studying mixed martial arts. Sometimes, being able to move at the right time is more important than being faster or stronger than someone else. The biggest thing I notice about really skilled people is not just that their technique looks great, but that it happens exactly when it’s supposed to.

Timing in natural phenology

Things are no different in the natural world. If a plant grows green leaves in the dead of winter, there won’t be enough sun for them to make sufficient food on their ‘investment’ of leaf growth. Those leaves will be a liability, because they could get damaged by freezing. Or, in the tropics, a tree leafing out in the dry season could lose precious water at a time when they can’t afford to. On the other hand, flowering during the dry season could be a great idea. Less competition, and fewer leaves to get in pollinator’s way.

Hibernating chipmunks that ‘wake up’ at the wrong time can risk starvation if they wake up out of sync. Being off-beat, they may miss the annual crops of nuts and seeds that they depend on. Similarly, a songbird that nests too late might risk its babies being injured by cold. Or, there may not be enough food left, because insect emergences have already come and gone.

Nesting too early, they may similarly miss the boat. Marine organisms have the same problem. Many of them need to time their release of reproductive cells like eggs and sperm so that prevailing currents are going in the right direction. Others need to come toward the surface to feed or mate on nights with or without moonlight. All of this depends on their needs, and the predictable rhythms of their environment.

Cues and Signals

It’s easy to tell from these examples that there can be dire consequences when living things get their timing wrong. These sorts of consequences mean that organisms that can get the timing right do better. This, in turn, means that they survive longer, have more offspring, pass on more of their genes to future generations. Over long periods of time, this sort of guiding force is called selective pressure. Evolutionary biologists would say that good timing is ‘selected for’ by the rapid change we see every day in nature.

Plants, animals, fungi, and other living things have all developed systems to get their timing right over thousands or millions of years.

Good timing typically involve cues; signals or patterns that trigger an organisms’ response. Some trees will put out catkins or other flowers when days get just long enough at certain times of year. Cicadas, living underground as nymphs, will crawl to the surface and metamorphose into adults once soil moisture and temperature get high enough in the spring or summer. Many species spend only a year underground, but periodical cicadas will spend up to 17 years! Larval fairy shrimp, living in suspended animation at the bottom of dry ponds, will spring to life in a matter of days when water is restored.

Knowing about these cues can help you predict when different happenings in nature will occur, and how you can stay one step ahead of the game. If you’re dying to see one particular bird, butterfly, or wildflower species, on the hunt for a certain mushroom or looking to witness a salmon migration, knowing your cues is a game-changer.

Using phenology in your time outside

Here are some ways you can take advantage of the power of when in your own study of nature:

Look for sources of timing or seasonal information

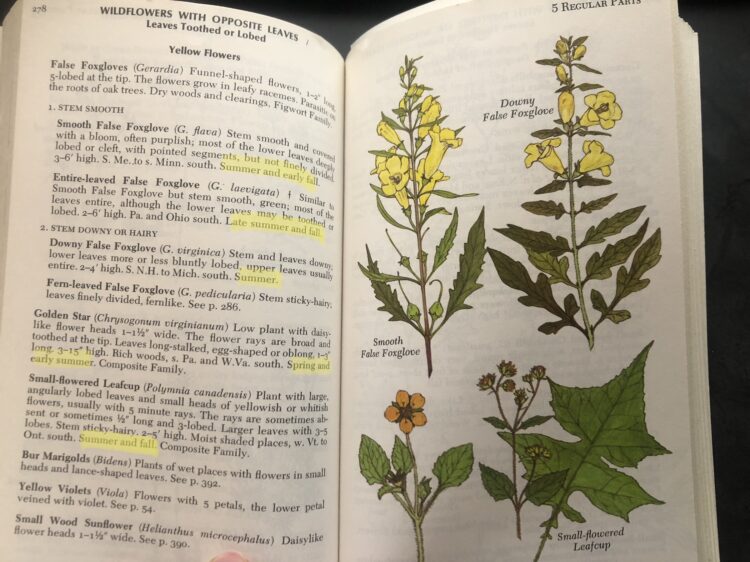

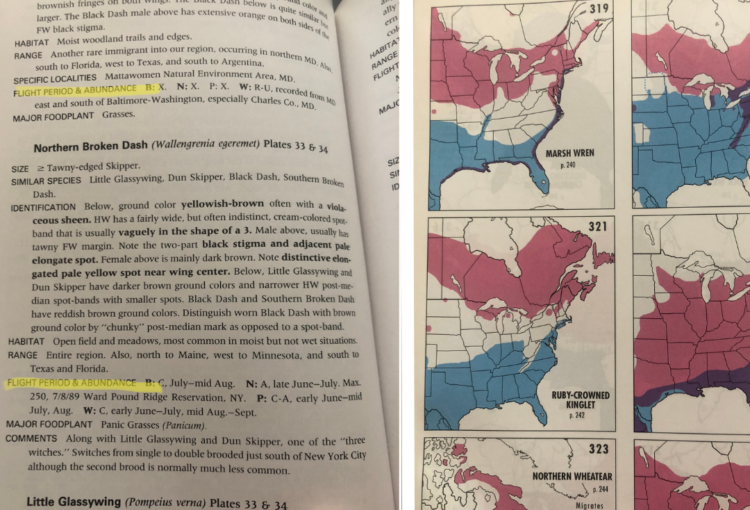

Many field guides and other reference texts will provide info on when you should expect to see certain species. This is a great place to start, although the specific timing will vary based on your locale. Some mobile apps like eBird and iNaturalist can get you more local info on what’s being seen in your area at what times.

Bird guides (right side) will often have charts that show a bird species’ distribution in different times of year; in this case, purple means year-round, blue means winter, and pink means summer.

Mark your calendar

Thinking ahead always pays dividends, especially if you have a busy schedule. When there’s some natural phenomenon I don’t to miss, I’ll often leave myself reminders weeks or even months ahead of time. That way, when it comes time for something I just can’t miss, I’ll have some forewarning. Some of this stuff happens so darn fast, it’s easy to miss otherwise!

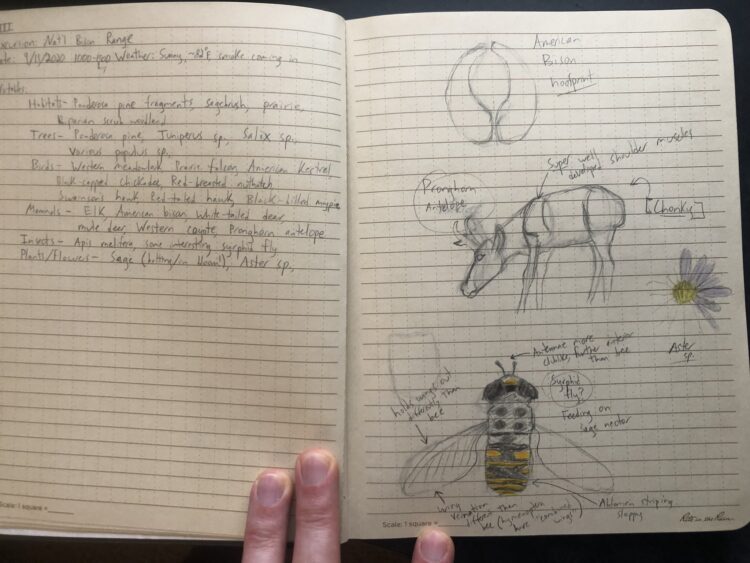

Keep a nature journal

There are many reasons to keep a nature journal, and lots of ways to use them. One of the easiest in my experience is just writing down the first day you saw something. First blooming wildflower of a given species, first honking group of geese flying by, first bugs marching into my living room.

If you’re in the same place for a few years, these lists can help you know when things are coming. Over longer periods of time (like Thoreau’s work) they can even tell us about how the environment is changing. Recently, I’ve tried to start working out my own 72 microseasons for my current home in the Georgia piedmont.

Thanks for reading about phenology!

What’s going on outside in your neck of the woods these days? Have you witnessed a cool nature happening at just the right time? Or maybe the wrong one? Let me know in the comments. As always, if you have additional topics you’d like to see covered in The Deep Stuff or any other blog category, please let me know here or via the contact page. Until next time!